Those Who Gave Their Lives: Arlington’s Fallen Sons in World War I

Used with generous permission. From Arlington Historical Magazine 2014, pages 23 – 44

“1917 – 1918

TO THE MEMORY OF

THOSE WHO SERVED IN

THE WORLD WAR

AND THOSE

WHO GAVE THEIR LIVES”

(Inscription on the Arlington War Memorial)

by ANNETTE BENBOW

The Arlington County War Memorial at 3140 Wilson Boulevard in Clarendon is comprised of plaques with the names of men and women who gave their lives in service to their country during times of military conflict. The first plaque commemorates thirteen soldiers and sailors from Arlington County who died in World War I. Additional plaques now include the names of Arlington’s dead from World War II, the Korean War, Vietnam, and most recently, those who died in Iraq and Afghanistan. Every year the living remember the dead here.

But who were the men whose names were first memorialized for their sacrifice? As the world remembers the one-hundred-year anniversary of the start of World War I, the Arlington Historical Society began research to uncover who these thirteen men were. Some remain a mystery, others have left a legacy that we can share here. On July 12, 1973, a fire at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, Missouri destroyed approximately 16-18 million official military personnel files. This affected eighty percent of U.S. Army personnel discharged between 1912 and 1960. No duplicates of these records were maintained. If any reader has any information about any of these men, please contact the Arlington Historical Society so that more about their short lives can be made known.

World War I started for the rest of the world in the summer of 1914. Despite efforts to remain neutral, the US entered the war in April 1917. The American Expeditionary Force, led by General John Pershing, began reaching Europe in July of that same year. Thirteen months later, fighting ended on November 11, 1918 on what is now known as Armistice or Veterans Day. Of the more than four million U.S. personnel sent to Europe, 116,708 American lives were lost; 53,402 were battle deaths but more than half, 63,114, were non-combat deaths, included training accidents and the Spanish flu.

Our thirteen young men reflect these numbers. The causes of their deaths are not all known, but of those for whom information is available, four died from illness—disease or the Spanish flu— and one died in an apparent training accident. There is an eyewitness account of one heroic death in battle but the circumstances of the remaining five deaths are as yet unknown. At least ten of the thirteen are buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

The commemorative plaque itself provides few clues. Eleven of the men were white. Two men were labeled on the 1931 plaque, in the vernacular of the day, as “colored.” Three were Navy men; the remaining ten were Army. Among them was an engineer, an aviator, and one was in a field artillery unit. Here are their biographies, their lives cut short by war and the details of each now incomplete due to the passage of time.

Harry Emory Vermillion

The first man to lose his life was twenty-seven year old Harry E. Vermillion, on March 15, 1918. Harry Emory Vermillion was born on October 23, 1890 in Washington, D.C. The federal census in 1900 revealed that at that time he lived at 1696 Columbia Road in Washington D.C. And, according to the next census, he was still living there 10 years later with his father and family but his mother, Lillian, was no longer living in the household. It is likely that she died, possibly because she gave birth in quick succession to four boys. In that era, childbearing was a leading cause of death for women. The census also recorded that Harry’s father, Charles, was a carpenter and the family had a live-in housekeeper. We can assess from this that Harry’s father made a good living and that the family was middle class. Seven years later, when Harry filled out his draft registration card on June 5, 1917, he was living in Cherrydale. He described himself as tall and slender with blue eyes and dark brown hair. He worked as a mechanic in the Signal Corps Laboratory in Washington which helped develop wireless radio communications and was a predecessor of today’s Naval Research Lab.

According to The Washington Post, Harry E. Vermillion departed for Camp Lee, near Petersburg, Virginia with 28 other draftees on November 1, 1917 at 12:16 in the afternoon. U.S. Army records show that most of his unit consisted of men from the Shenandoah Valley and Tidewater areas. Private Vermillion died at Camp Lee on Friday, March 15, 1918 at 27 years of age. He was in E Company, 318th Regiment, 80th Division of the U.S. Infantry. His division, known as the “Blue Ridge Division,” began leaving Camp Lee for Europe on May 17, 1918 without him.

The cause of Harry’s death is unknown. However, according to a newly married wife visiting her husband at Camp Lee, conditions in the camp were “miserable.” Recent research on the effects of the influenza pandemic on troops in World War I shows that 77 percent of deaths from influenza and pneumonia at Camp Lee were among men with less than three months in service. It is possible that Harry died of a training accident, but it is much more likely that he died of the Spanish Flu.

The name, “Spanish flu” is misleading. To maintain morale, wartime censors minimized early reports of illness and mortality in Germany, Britain, France, and the United States, but newspapers were free to report the epidemic’s effects in neutral Spain. This created the false perception that the flu began in Spain; hence this pandemic became known as the Spanish flu. Flu outbreaks usually affect the young, elderly, or already weakened patients, but the 1918 pandemic predominantly killed previously healthy young adults—including troops. Military training camps were natural concentrations of likely patients and these camps soon became breeding grounds for the disease.

Harry’s funeral was held the Monday after his death at Epiphany Church in Cherrydale. His father was not the only mourner. According to a local newspaper account, “A large and sorrowful crowd gathered at the church.” On the flag-draped casket was a guitar and the newspaper noted that “no more on earth would they hear him play.” Harry was laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery.

Henry Smallwood

The second Arlington resident to die during the war was Henry Smallwood. He died sometime before March 23, 1918. The only document uncovered was an insurance company record of a death benefit payment of $1200 to a claim made prior to March 23. Henry lived in Clarendon. He was a private in the army but no further details are available.

Edward J. Smith

The next Arlington boy to lose his life was Edward J. Smith. He died on the night of May 25, 1918. As with the others, there is little available information about Edward. He was a private in Battery A in the 100th Field Artillery Division. According to army records, the 100th Field Artillery Division was composed of National Guard units from the District of Columbia. He died at 22 years of age on the night of May 25-26, 1918 at Camp McClellan, Alabama. The cause of Edward’s death was listed on the death certificate as “disease or other cause.” He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Units from the 110th Field Artillery Division training at Camp McClellan, Alabama on February 27th, 1918

Credit: Library of Congress

Camp McClellan, where Edward was based, was one of 31 camps formed to quickly train men to fight in World War I. It is likely that the same poor conditions that may have exposed Harry Vermillion to the deadly flu also existed at Camp McClellan. The camp consisted of hastily built wooden buildings for headquarters, mess halls, latrines, and showers, with rows of wooden-floored tents to house the troops. The first troops arrived in late August 1917; by October there were more than 27,000 men from units in New Jersey, Virginia, Maryland, and the District of Columbia training at the camp.

Oscar Lloyd Housel

Captain Oscar L. Housel was the fourth Arlingtonian to fall in service to his country. Oscar Lloyd Housel was born on July 5, 1877 in Galesburg, Indiana. He attended the University of Illinois where he majored in mechanical and electrical engineering. He was a member of the Army and Navy Club and earned the title of Lieutenant Colonel of the University Regiment—likely a form of today’s Reserve Officers Training Corps or ROTC.

He interrupted his education by enlisting in the U.S. Army on April 26, 1898 to serve in the Spanish American War. According to his enlistment record, he got his first taste of Virginia in July 1898, when his unit, Company C in the 6th Illinois Infantry, was sent to train in the newly established Camp Alger near what is today the Dunn Loring area of Falls Church. Accounts of Camp Alger described deplorably unsanitary conditions at the camp. Perhaps that was what spurred Oscar to be assigned to the Army Hospital Corps where he served in the invasion of Puerto Rico. He was discharged on November 6, 1898.

Oscar Housel’s graduation photograph from the University of Illinois, Urbana

Credit: University of Illinois Veterans Memorial Project

Oscar was apparently among the middle class, judging from his ability to travel, because in September 1900 he returned from a trip to England aboard the S.S. New England. This was a time when most middle class families took extended trips to Europe. Oscar’s passport was issued on June 11, and on it Oscar wrote that he planned to spend several months traveling in Europe. So he apparently spent the summer there and returned to Illinois in time to start his last year of undergraduate work. He described himself in his passport application as being 5 feet 8 inches tall with blue eyes and brown hair. He graduated in 1901 from the University of Illinois at Urbana with a degree in engineering. He is shown here in his graduation photo.

After graduation, Oscar worked for a time as an Assistant in Military Science at the university. The next year he was in the Testing Department of General Electric and served in his reserve military capacity as the Post Engineer at Fort Yates in North Dakota and Fort Yellowstone in Wyoming, according to a University of Illinois publication providing information about alumni. On June 1, 1904, Oscar married Marion Alberta Nelson, a native of Washington, and they had a son named Robert who was born the following year, on July 3, 1905. By then Oscar was employed at the Navy Yard as an electrical engineer and draftsman for the Bureau of Yards and Docks, where he made $1,200 per year.

Initially, Oscar made his home at 39 Seaton Place, N.W. Washington, D.C., but by 1910, he had moved to Clarendon where he and his family were renting. His occupation was noted in the 1910 census as an electrical engineer working for the “Public Service Commission.” In August 1914, Oscar was appointed assistant engineer in the valuation bureau of the Public Utilities Commission of the District of Columbia.

As a member of the D.C. Engineer Reserve Corps, Oscar again was called to duty for service in America’s next military conflict, World War I. This time he was in Company A of the 38th Engineering Corps. He reported for duty in Washington, D.C. on November 17, 1917. According to U.S. Army records, he died on August 19, 1918 at Bordeaux, France from disease and was buried in the American Cemetery in Talence, Gironde, France. No historical record revealed what disease he died from, although influenza was again the most likely cause.

What might Oscar have done as a member of the Engineering Corps? During World War I, engineers were in charge of repairing the war zone infrastructure to expedite troop movements. The Corps repaired bridges and roads; maintained communication lines; removed land mines and booby traps; built shell, gas, and splinter-proof shelters; and constructed or removed barbed wire. They also built hospitals, barracks, mess halls, stables, target ranges, and repaired miles of train tracks. These duties left the men little time for front line duty and they were not relied upon for combat. Nevertheless, Allied forces depended upon their support.

On November 15, Captain Housel was returned home from his grave in France to be re-interred at Arlington National Cemetery. The D.C. District Building lowered its flag to half mast and the District’s electrical department closed all day to honor the captain. Members of the Vincent B. Costello Post, American Legion served as pall-bearers.

Oscar Housel is not only commemorated here in Arlington, but in two other memorials.

• His name is inscribed on a memorial sculpture called “The Supreme Sacrifice,” that was dedicated in April 1920 in the D.C. District Building. Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby and Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels addressed the crowd. President Wilson’s daughter, Margaret, unveiled it. Sculptor Jerome Connor described his work as “an undying American soldier just before he makes the supreme sacrifice.” The names of thirteen men who worked in the District and died in World War I are engraved on the statue along with the department for which each worked. Oscar’s entry reads: “Capt. Oscar L. Housel, electrical department.”

• In 1923, his name, along with scores of other University of Illinois students’ names, was also enshrined on a column of the University of Illinois Memorial Stadium, built in 1923 as a memorial to Illinois students who died for their country during World War I.

Archie Walters Williams

Details about the next Arlington boy, Navy Yeoman Third Class Archie Walters Williams, are also limited. He died of influenza (noted also as bronchial pneumonia on his death certificate) in the US Naval Hospital in Philadelphia on September 30, 1918. Born in 1898, he was just nineteen years old. On April 25, 1917 Archie enlisted as a member of the US Navy Reserve Force in Washington, D.C. No records were found to say how he served his country or to which ship he was assigned. However, he most likely saw active service, because in 1920 the French government honored his memory and sacrifice and that of scores of others at a ceremony held at the Central High School auditorium in the District.

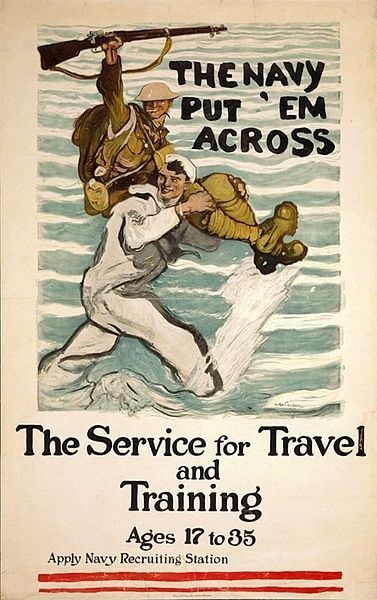

Navy recruitment poster

Credit: Hampton Roads Naval Museum

The U.S. Navy Reserve Force, or Navy Militia, was formed by the Navy Act of March 3, 1915 and Archie enlisted just nineteen days after the United States declared war on Germany. All state navy militias, including the District’s, were activated and Archie may have been influenced by the profusion of enlistment posters that sprang up like the one shown. Young men who enlisted about the same time as Archie later recounted that within three months of enlistment, navy men were trained and assigned to US ships on their way to France protecting convoys of US troops from German U-boat attacks. Naval reservists were also radio operators and aviators but many more served aboard ships protecting troop convoys bound for Europe. It is likely that this is the service for which the French government paid homage to America’s sons.

Yeoman Williams was only in the hospital for four days, according to his death certificate— testament to how quickly the influenza ran its course in its victims. His parents, William and Emma Williams of Cherrydale, held his funeral on October 14 and he was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Frederick Wallis Schutt

Frederick Wallis Schutt was the next Arlington military man to die in World War I. Frederick was born on May 24, 1900. The 1900 Federal Census recorded that he had an older sister, Marie, and later he had a younger sister, Cora, who was born in 1902. In 1900 the Schutt family, including his mother and father, Belle and Wallis Schutt, lived in Cherrydale. When a commuter railroad was established in 1906 connecting the District with the emerging suburbs, the Schutt family property was the first area developed along what are now Lee Highway and North Quincy Street. The first residential subdivision in Cherrydale included twelve lots known as Schutt’s Subdivision along the north side of what is now 20th Street, North. The 1900 census also listed his father’s occupation as dairyman, but by 1910 the census recorded that Mr. Schutt was a general contractor, perhaps reflecting the economic changes in the area as farmland began to be turned into suburbs.

Frederick enlisted as an apprentice seaman in D.C. on July 31, 1918. He died at the Naval Hospital at the Naval Base in Hampton Roads, Virginia from pneumonia or “respiratory disease” on October 7, just over a month before the 1918 armistice was declared. This may have been caused by the influenza. He was interred at Arlington National Cemetery on August 4, 1921

Frederick Schutt’s family planted the First Memorial Tree in Virginia to honor World War I casualties. His aunt, a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution, Ellen B. Wallis, planted the tree in Cherrydale in memory of her nephew on May 25, 1919. This was the first of 6,000 memorial trees to be planted by the Rotary Club of Virginia and it was registered in the national honor roll of the American Forestry Association.

Harry R. Stone

Only five days after Frederick Schutt died, Arlington lost its next soldier. Harry Stone was born in Washington, D.C. in December 1895. The 1900 census recorded that he lived with his mother and father, Lizzie and George Stone, and his two sisters and three brothers at 1037 30th Street. His father was a barrel dealer. In 1915, Harry was a bugler in the boy scouts, and in October of 1915, at a flag raising by Troop No. 48 at the dedication of a new boy scout clubhouse, Harry recited the history of the troop.

On July 4, 1917, the Washington Times printed an interview with Harry’s mother on the front page. Now living in Clarendon, she was making the supreme sacrifice of motherhood by encouraging her two sons, Harry and James, both below conscription age, to enlist in answer to President Wilson’s call to arms. She said she did not believe that young men of Virginia were coming forward fast enough and said it was up to someone to set an example in patriotism in Virginia. Harry Stone, not yet 20, joined Company H, Third Regiment in the District’s National Guard. His brother James joined the Navy.

Two years later, the Washington Times announced that Company H of the 162nd Infantry, composed of men formerly of the old District National Guard, arrived from France on May 20 on the transport Rochambeau. Harry Stone was not among the 241 men who returned to America that day. According to the company commander, Company H sailed for France on December 11, 1917. The men from the District were put in charge of the direction of troop movements out of Lehavre [sic], France. They were attached to a British camp and some of the men were transferred to the First Army Corps. Harry Stone died on October 12, 1918, found drowned in a canal in France along the Western Front. The officer recounted that the men never saw direct action and it is unknown how Harry died. Private Harry Stone was interred at Arlington National Cemetery on August 4, 1921.

John Lyon

Captain John Lyon is the most decorated of the Arlington men who died in World War I. He died trying to save another man’s life on October 15, 1918, just three weeks before the armistice. John was born in Ballston on April 2, 1893. His father, Frank, was a lawyer, a newspaper publisher, and a land developer, as today’s Lyon Park can attest. John went to Western High School in the District at 35th and R Streets NW (what is now the Duke Ellington School for the Arts). According to reminiscences of his younger sister, Margaret, John and their older sister, Georgia, rode the electric cars to Rosslyn, the end of the line, then walked across Aqueduct Bridge to their schools. He graduated in 1910.

After graduation, John attended the University of Virginia for two years. The first year he was elected an officer of the student body and the next year he was elected secretary of the Jefferson Literary Society. He returned to northern Virginia and became editor and publisher of The Alexandria County Monitor for two years. He also studied law at night at Georgetown University. Even though the U.S. did not get directly involved in the war until 1917, many Americans, such as John, heard the call and volunteered to serve in France in 1915. John’s passport application is witnessed in signature by his father, so Mr. Lyon must have at least condoned his son’s early departure, if not encouraged it.

In his passport application, dated April 30, 1915, John wrote that he planned to return to the U.S. within twelve months and intended to go to France to be an ambulance driver in the Hospital Corps. He may have been moved by news reports of increasing German aggression, first of German Zeppelin air raids on England, followed by Germany’s declaration of a submarine blockade of Great Britain that declared that any ship approaching England would be considered a target. John described himself in the application as being 5 feet, 7 ¾ inches tall, with brown eyes and medium brown hair. He also stated that he was living with his parents at Lyonhurst, their stately mission-style home built in 1907 at what is now 4651 North 25th Street. This residence was said to be the first home in the county to have electricity.

John left the U.S. in mid-May 1915 for France. He wrote home often and his father published two of his letters in The Alexandria County Monitor. In a letter to his younger sister dated August 1915, John wrote that he was based in Westvleteren, Belgium, just a few miles from Dunkirk. He went on “evacuation runs to carry the” wounded “from the field hospitals” that may have been houses or barns “to bigger ones further back.” He downplayed how close he came to the front lines and the danger involved by writing that he did a lot of chauffeuring of doctors. However, he admitted that he and his fellow ambulance drivers only went out at night because in the daytime Germans would see them and “mistake” the ambulances for ammunition or supply wagons. He said that as they approached the front lines “things certainly take on a grimmer and more serious aspect.” He wrote that closer to the front where they picked the wounded up, “They never laugh down there. All is grim, and the poor wrecks … sing no songs and bring no captured banners back; only memories of lives offered on firey alters [sic].” In an earlier letter written in June of 1915 to his mother, John described a trip along the Seine that bears little resemblance to the candid description to his sister of what he saw near the front. For his mother—and perhaps for military censors—he described driving two officers to the suburbs of Paris and strolling through a park looking at flowers and trees.

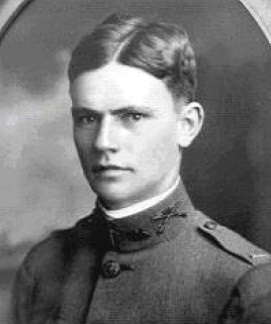

Captain John Lyon

Courtesy J. Gary Wagner

John renewed his passport application at the U.S. Embassy in Paris in November 1915 for six more months of hospital work, but a passenger list for the U.S.S. Philadelphia showed that he returned to the U.S. on December 16, 1915. He enlisted in the U.S. Army and was stationed for six months on the Mexican border.

A letter to the Washington Times dated August 17, 1916 from John Lyon, posted from Brownsville, Texas, offers a glimpse of his personality. His letter lightheartedly asked that Sarah Bernhardt, a famous French singer and actress, who had recently toured America, visit U.S. troops along the Mexican border just as she had visited French troops in France. His letter gently complained that life for Company G of the First Volunteers was easy duty but he also may have hinted that he missed home by writing, “Life here is as quiet, so far as danger in concerned, as it was on the farms or in the villages back home.”

Even before Lt. Lyon arrived in Texas, the Mexican border was patrolled by the U.S. Army. In March of 1916, Mexican revolutionary leader Pancho Villa raided Columbus, New Mexico, killing ten civilians and eight soldiers. General John Pershing led an expedition into Mexico to capture him and U.S. troops remained to patrol the border against more incursions. The border remained troublesome to the U.S. military. Germany had long sought to incite a war between Mexico and the U.S. to divert American attention and slow the export of American arms to Europe. In February of 1917, the British government exposed a coded telegram from German Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmermann to the German ambassador to Mexico instructing the ambassador to approach the Mexican government with a proposal that Germany would provide funding and assistance for Mexico to reconquer Texas and the Southwest if it looked like the U.S. was about to enter the war.

These same troops under General Pershing, including John Lyon in the First Virginia Regiment, were trained, had experience, and were the best prepared to deploy to Europe once the U.S. declared war in April 1917. Lyon returned home briefly and was then promoted to sergeant in his company, departing with his men for Camp McClellan, Alabama on September 25, 1917. (John arrived at camp several months before fellow Arlingtonian Edward Smith.) From there Lyon shipped out to France. Probably because of his experience and his level of education, he was promoted to lieutenant and assigned to the machine gun company of the 116th Infantry of the 29th Division. Composed of men from both the north: Maryland and the south: Virginia and North Carolina, the 29th Division was nicknamed the “Blue and Gray” a reference to the blue uniforms of the Union and the gray uniforms of the Confederate armies during the Civil War. These fresh troops were immediately deployed to the front. Letters from John to his family led them to believe that he served almost the entire time in front line trenches.

In late September 1918, the 29th Division was ordered to join the U.S. Army’s Meuse-Argonne offensive. This campaign was part of the final, and most bloody, Allied offensive of World War I. For the next 47 days— including the rest of Lt. Lyon’s life—the 29th Division advanced seven kilometers (a little more than four miles). The battle was the largest in United States military history to date and involved 1.2 million American soldiers. Thirty percent of the 29th Division became casualties, with 170 officers and 5,691 enlisted men killed or wounded. John Lyon was one of those men who died in this final Argonne push to break through the German lines. The Argonne offensive helped bring an end to the war.

Ten days after peace was declared, The Washington Post reported that John Lyon’s parents had received notification from the War Department that their son had been killed in action on October 15. Months later, Frank Lyon received a letter from Major H. L. Opie of the 116th Infantry. The letter told the bereaved family how Lt. Lyon had died near Bois De La Grande Montagne.

Lieutenant Lyon had the guns of his platoon posted in partial shelter on my left, against counter attack. He saw me fall wounded and leaving his guns, ran directly to my assistance in the face of certain death. He was killed by the fire of an enemy machine gun and fell within a few feet of me.

For this act of valor, on April 20, 1920, Lt. John Lyon was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the second highest award that can be given to a member of the U.S. Army. It is awarded for “extraordinary heroism while engaged in action against an enemy of the United States.” The Distinguished Service Cross was established in January 1918 specifically to honor those who deserved recognition for their heroic service in World War I.

Besides Arlington County’s memorial to its dead in World War I, several other memorials in Washington D.C. and in Arlington honored John Lyons:

- In December 1920, Georgetown Law School alumni marched from the law school to Dahlgren Chapel for a special military mass attended by students, alumni, and the relatives of those who had died.

- In 1921, the American Legion engraved the name of each of Washington D.C.’s war dead on a copper plate to be mounted on a concrete post near a tree dedicated to each on Sixteenth Street between Allison and Alaska Avenues, N.W. A dedication ceremony was planned for Decoration Day (now called Memorial Day).

- In June 1921 Georgetown again commemorated the 28 law students who died in the Great War with a bronze tablet inscribed with their names and placed in the law library.

- In 1927, Georgetown also planted 53 elm trees as a living memorial to each of the students.

- Finally, on November 11, 1934, The Veterans of Foreign Wars instituted the John Lyon Post No. 3150 in Arlington to honor him.

John Lyon was laid to rest among his family in Blandford Cemetery in Petersburg, Virginia. The inscription on his gravestone says simply, “In the Argonne.”

Frank Edward Dunkin

Frank Edward Dunkin died less than two weeks after John Lyon, on October 28, 1918. Frank was born on February 21, 1891 in Fort Wayne, Indiana. His father had been born in New York and served in the Civil War as a Second Lieutenant in the 162nd New York Infantry. According to the 1900 census, the family owned their home at 148 Seventh Street, Washington D.C. N.E. As a youngster, Frank Dunkin took piano lessons with Mrs. Wilma Benton-Smith and for several years each spring he performed in a recital with her other students. In 1902, Frank’s father, Thomas, died and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. In April of 1910, the census showed that the family no longer owned a house but was renting a home at 709 Third Street, N.E. in Washington D.C. It may be that the family fell on harder times with no senior bread winner. Frank, then 19, was a copyright clerk in the Library of Congress.

At 26 years of age, Frank registered for the draft on June 5, 1917. By then he was living in Clarendon. His stated profession was a statistician, but records do not list his employer. He was single. He also noted on his application that he had previous military service as a navy yeoman for three years and 19 days. He described himself as being tall and of medium build with gray eyes and brown hair. Frank’s maturity at 26 and his professional work experience likely propelled him to quick promotion to corporal in the 54th Infantry Regiment of the 6th Division. He shipped out with his division to France in July, 1918.

Frank Dunkin’s service patch in the “Sight-Seeing Sixth”

www.usmilitariaforum.com

The service patch for the 6th Division that Corporal Dunkin wore on his shoulder was a small six-pointed red star similar to the Star of David, with a small “6” in the center. Once the 6th Division arrived in France, these inexperienced troops continued their training, which mostly consisted of marching throughout western France. British and French veterans, usually non-commissioned officers, taught the green American troops how to survive trench warfare, a skill few Americans then had acquired. The division marched so much during this training that they earned the nickname the “Sight-Seeing Sixth.” Finally, on August 31 the division was assigned to the Vosges mountain region east of the Argonne to defend 21 miles of the front line.

The troops patrolled rough terrain and were often behind the German lines. They faced daily German artillery bombardment and frequent German raids that used flame throwers, grenades, and gas. Just before the Meuse-Argonne Offensive began, the 6th Division cemented its reputation when it was ordered to conduct fake marches to make the enemy think that a major attack would occur in the Vosges region rather than in the Argonne. The troops were often under heavy enemy artillery and air bombardment. Corporal Dunkin was killed just before the final Allied push to end the war began on November 1.

Frank Dunkin was originally buried in France, but he was re-interred with his father in Arlington National Cemetery in May 1921. In December 1920, the Library of Congress planted a memorial tree, a Japanese elm, on the south side of the Library of Congress to honor four of their staff who were killed in the war. Like John Lyon, Frank Dunkin’s name was also inscribed on the copper plates near trees planted on 16th Street that were dedicated to DC’s war dead in 1921.

Irving Thomas Chapman Newman

Irving Newman and his family

Credit: Arlington Historical Society

Twenty-two year old Irving T.C. Newman died on November 2, 1918. Irving was born on February 20, 1896 in Washington, D.C. According to the 1900 census, he was living in D.C. with his mother and two younger brothers: Eugene, who was two years old, and Allen, who was three months old when the census was taken. The head of the household was not his father but his mother’s father, Chapman Godfrey. His mother, Mary, had been married for five years. His father, George R. J. Newman, was living in D.C. on B Street., S.W. and he was an engineer for the government. In the 1910 census, Irving’s father was listed as living with his family in D.C. on Virginia Avenue and Irving was the oldest of now four sons, including one more brother, James. George stated that his profession was a stationary engineer. This is someone who operates heavy machinery and equipment that provide heat, light, and power in large buildings such as factories, offices, hospitals, warehouses, power generation plants, or other commercial buildings. The history record offers no hints about why Thomas’s father was not recorded as living with his family in 1900.

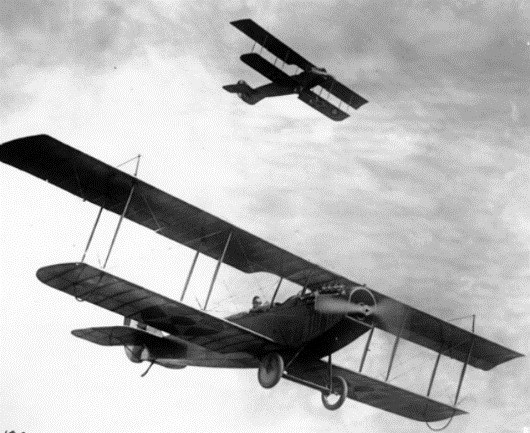

On June 16, 1916, Irving graduated from McKinley Manual Training School at 7th Street and Rhode Island Avenue in the District. McKinley Manual Training School, which would become Robert Gould Shaw Junior High School, was the city’s first purpose-built manual training school. Ten days later, Irving was getting ready to ship out with the Signal Corps to the Mexican border as a private. Irving joined the Washington D.C. Signal Corps and served in the Punitive Expeditionary Force to quell Pancho Villa’s activities along the border. Private Newman’s duties in the Signal Corps are unclear. He might have kept communications up and running between the US side of the border and Pershing’s camps in Mexico. He could have been one of the soldiers marching into Mexico to find Pancho Villa in the Sierra Madre mountains in Chihuahua. He would almost certainly have seen aircraft used for the first time in military operations. As a graduate of McKinley, he may have worked on them. Because of the thin dry air in the mountains, the aircraft—often Curtiss JNs or “Jennys”—needed constant care and attention.

Irving returned to D.C. and went to work for the Department of Commerce in January 1917 as a laboratory apprentice for a salary of $540 a year. The 1918 Washington D.C. City Directory listed Irving Newman as residing in Cherrydale.

Two Curtiss JN-4D Jennys above a training camp in Texas, c. 1918.

Credit: San Diego Air and Space Museum

He signed up for the draft and rejoined the US Army Signal Corps, this time as a pilot in its Aviation Corps. History records that Second Lieutenant Irving Newman was killed while training at Camp Mabry in Austin, Texas. The death certificate stated that he died of a fracture of the base of the skull, or a broken neck. U.S. Army Signal Corps records reflect that he was flying a JN-4D aircraft that crashed.

The JN-4D was a Curtiss “Jenny” like those used in the Mexican border action. These aircraft were considered the Model T of the skies because they were the first aircraft purchased in quantity by the American military. They were used to train over ninety percent of American pilots during WWI. The Curtiss Jenny biplane was not easy to fly. It was under-powered, and its nose tended to dip during turns. It was considered an unforgiving airplane, as evidenced in the many crashes that took place while training. Strictly used as a trainer, the Jenny never saw service in combat during the war. Second Lieutenant Irving T. C. Newman died training in a Jenny after having served his country honorably elsewhere. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Arthur C. Morgan

Arthur C. Morgan died on December 3, 1918, three weeks after the Armistice. Unfortunately there are few surviving records for Arthur. He was born in Langley, Virginia on June 28, 1887, so he was among the oldest of Arlington’s veterans lost in World War I. According to the 1910 Census he was a laborer working for the Arlington Experimental Farm. A member of the county’s African-American community, he was listed as single in the 1910 census, but when he registered for the draft on June 5, 1917, he was married and living at Hall’s Hill. He described himself as being of medium build with black hair and black eyes and he admitted he was slightly balding.

View of the Arlington Experimental Farm, on the southern bank of the Potomac River, October 1907. Part of this land is now the site of the Pentagon. The Custis-Lee Mansion can be seen on the hillside in the distance.

Credit: Library of Congress

The Arlington Experimental Farm was the main research facility for the US Department of Agriculture in the Washington area from 1900 until 1941. Experiments in fertilization, farming methods, and irrigation took place on a portion of land that had once been the Custis-Lee estate. The facility was under the direction of the USDA’s Bureau of Plant Industry, so no livestock were there. As a laborer, Arthur may have worked to install the tile drains under the experimental plots or to build greenhouses, barns, or laboratories. (In 1941, the activities of the Arlington Experimental farm were transferred to the Agricultural Research Center in Beltsville, Maryland and the property was ceded back to the War Department. The site of the farm is now the south parking lot of the Pentagon.)

Private Morgan was re-interred at Arlington National Cemetery on August 3, 1920. The cemetery’s “Report of Interment” form states that he was in Company A, 550th Engineer Service Battalion. When he died on December 3, 1918, he was first buried with hundreds of other Americans in American Cemetery #153 in Lambezellec, Finistere, France.

When President Wilson stood before Congress and asked Congress to declare war on the German Empire on April 2, 1917, he declared that “The world must be made safe for democracy.” These words resonated with many African-Americans who viewed the war as an opportunity to bring about true democracy in America. As the United States mobilized for war and the draft began, most African-Americans saw the war as an opportunity to demonstrate their patriotism and their place in the country as equal citizens. Even though Arthur was the head of the family and likely the only breadwinner, his registration for the draft in early June 1917 may be testament to those sentiments.

The U.S. armed forces were rigidly segregated during World War I. Still, many African-Americans eagerly volunteered to join the Allied cause. By the Armistice with Germany on November 11, 1918, over 350,000 African-Americans had served with the American Expeditionary Forces on the Western Front. The U.S. Army General Staff believed that since most blacks had been manual laborers as civilians, they should be laborers in the Army, so black service troops received little or no combat training. As a result, approximately ninety percent were relegated to support roles and did not see combat. Unlike white draftees, when Arthur reported for active duty he was almost certainly given fatigue uniforms and immediately put on work details.

Nevertheless, among the first American troops to arrive in France in July 1917 were African-American stevedores. They worked day and night to load and unload crucial supplies, bringing war materiel ashore at the docks of Brest, St. Nazaire, Bordeaux, and other French port cities. Soon they became known as Services of Supply (S.O.S.) units and they provided the basis of the military logistics system in Europe. The S.O.S. also dug ditches, cleaned latrines, transported supplies, cleared debris, and buried rotting corpses. Their hard work earned official praise but did not warrant promotion or reassignment. Blacks were limited to the ranks of corporal and below. Arthur Morgan died a private.

When the war ended on November 11, 1918, most combat troops came home as soon as transportation could be arranged. Service troops, however, particularly blacks, remained to clean up the battlefields, tear down unneeded fortifications, and dismantle military installations. It was backbreaking, dirty, dangerous work. We do not know how Private Morgan died on December 3. He may have been injured or he, like thousands of others, may have succumbed to the influenza that still raged among the troops.

Robert Bruce

Robert Bruce was the last Arlingtonian to die in service to his country in World War I on December 23, 1918. We know precious little about him. His tombstone in Arlington National Cemetery reveals that his wife’s name was Eva and says he was a corporal in Company D of the 2nd Cavalry Regiment, also known as the Second Dragoons. During World War I, the regiment participated in several battles, including the last German offensive, the Aisne-Marne Offensive. Corporal Bruce’s unit was among the last elements to engage the enemy while mounted on horseback. This Allied victory signaled the beginning of the end for Germany, because not only did the Germans fail to win this battle, they lost ground to the Allies. Disheartened, some German commanders concluded that the war was lost and the German Army did not launch any additional large-scale offensives during the remainder of the war. Aisne-Marne took place over the course of July 15 through August 5, 1918. Casualties were high, more so among the German forces than among the Allies. Germany lost 168,000, France suffered 95,000 casualties, Britain incurred 13,000 losses and the U.S. 12,000. Corporal Bruce may have sustained injuries that ultimately caused his death several months later. It is also possible that he, like so many others, fell ill after battle and died of the influenza.

What little else we know about Robert Bruce emerged in 1931 when Arlington County unveiled the tablet inscribed with the names of the thirteen men killed in the war. The Washington Post reported that Katherine Bruce, the thirteen-year-old daughter of Corporal Bruce, unveiled the memorial upon which her father’s name was inscribed. Katherine would have been born in 1918. A baby when her father left for the war, it is possible that her father never had the chance to hold her.

Ralph Lowe

One last name appears on the plaque, that of Ralph Lowe. Like Arthur Morgan, Ralph is labeled as “colored” and separated on the plaque by a space below the names of the white men. No other details of his life are available, but thanks to this plaque, we know he also gave his life in service to his country. The plaque tells us all we can find. He served in the U.S. Army. Like all the others, he died and his name, at least, is remembered.

Epilogue

On a hot late-summer day, the author spent an afternoon at the Arlington National Cemetery searching for each of the graves of the eleven men known to be buried there. John Lyon is buried in his family’s plot in Petersburg, Virginia and we do not know where Ralph Lowe is buried. The other men are buried in sections 3, 17, 18, and 19. Ralph Morgan is buried in section 19, once known as the “colored section” of the cemetery. Frank Dunkin is buried with his father, who was a veteran of the Civil War for the Union and who died when his son was a child. Harry Vermillion, Edward Smith, and Archie Williams are buried a stone’s throw from each other. It is unlikely that any of the Arlington men who went to fight in World War I ever met each other, but in death, they lie together, an easy walk from each other. The sections where these Arlington men are buried are quiet. Few visitors seek graves that are almost a hundred years old. Few have a recollection that some distant ancestor offered his life for his country or have any thought of the kind of men they may have been or what they experienced in training or on the battlefield. Neither can we know any of this about them. But, like Ralph Lowe, even if we only know their names, we can remember them.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank J. Gary Wagner, Adjutant, John Lyon VFW Post 3150 in Arlington for sharing a treasure trove of details about John Lyon and his military service, including rarely published copies of his letters home. Dr. John T. Snow of Ohio University also provided invaluable help and perspective in conducting research using military records of the era. Steven Suddaby, past president of the World War I Historical Association, pointed me to a plethora of useful online research links for World War I military records. The Arlington Public Library Center for Local History offered the starting point for much of this research. Finally, Dr. Mark. E. Benbow, Assistant Professor of History at Marymount University, provided historical context for the events surrounding the lives of these thirteen Arlington men.

ENDNOTES

- Vermillion Federal Draft Registration Card, on www.ancestry.com (Accessed on August 1, 2014).

- 1900 Federal Census, on www.ancestry.com (Accessed on August 1, 2014); 1910 Federal Census, on www.ancestry.com (Accessed on August 1, 2014).

- “Alexandria Sends 29 More to Camp,” The Washington Post, October 31, 1917, p. 4.

- “Eightieth Division (National Army),” www.newrivernotes.com/topical_history_ww1_oob_american_forces.htm (Accessed on August 1, 2014).

- Roger Heller, “My Father and World War I,” http://www.worldwar1.com/tgwscontr/rheller.htm (Accessed on August 1, 2014).

- Peter C. Weaver and Leo van Bergen, “Death from 1918 Pandemic Influenza During the First World War: A Perspective from Personal and Anecdotal Evidence,” The Journal of Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses, June 27, 2014, on http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/irv.12267/full (Accessed on June August 1, 2014).

- “Honor to Soldier Dead,” on www.ancestry.com (Accessed July 30, 2014).

- “Life Payments Localized: Claims Paid Recently, Distributed by States, Cities and Towns,” The Insurance Press, April 17, 1918, p. 14.

- “War Dead Databases,” on http://1914-1918.invisionzone.com/forums/index.php?showtopic=8962&page=9 (Accessed on August 1, 2014).

- Smith death certificate, on www.ancestry.com (Accessed on 1 August 2014).

- Mary Beth Reed, Charles E. Cantley and J. W. Joseph, Fort McClellan: A Popular History (New South Associates, 1996), pp. 71-83.

- Passport Application, 1900, on www.ancestry.com (Accessed on July 6, 2014).

- “1902 University of Urbana,” on http://archive.org/stream/illio1902univ/illio1902univ_djvu.txt (Accessed on August 2, 2014).

- Dominion Line List or Manifest of Alien Immigrants for the Commissioner of Immigration, August 8, 1900, on www.ancestry.com (Accessed on August 3, 2014).

- Housel graduation data, on www.ancestry.com (Accessed on August 3, 2014).

- ”University of Illinois (Urbana-Champaign campus),” 1901, p. 83, on http://books.google.com/books (Accessed on August 3, 2014).

- “The Alumni Record of the University of Illinois at Urbana,” p. 284, on http://www.mocavo.com/The-Alumni-Record-of-the-University-of-Illinois-at-Urbana/261177/329 (Accessed on August 2, 2014).

- Official Register of the United States, Containing a List of the Officers and Employees in the Civil, Military, and Naval Service Together with a List of Vessels Belonging to the United States, 1903, Vol. 1, on www.ancestry.com (Accessed on July 6, 2014); Estimates of Appropriations, 1903, p. 455, on http://books.google.com/books (Accessed on July 6, 2014).

- Washington, District of Columbia City Directory, 1905, on www.ancestry.com (Accessed on July 6, 2014).

- 1910 Federal Census, on www.ancestry.com (Accessed on August 2, 2014).

- Army and Navy Register and Defense Times, Vol. 62., p. 626, http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924069767071;view=1up;seq=632 (Accessed on August 2, 2014).

- The University of Illinois Veterans’ Memorial Project, http://www.uiaa.org/illinois/veterans/display_veteran.asp?id=82 (Accessed on August 2, 2014); World War I Casualties Of American Army Overseas Reported On September 11, 1918 http://www.genealogybuff.com/misc/ww1/il-ww1-ago-casualties103.htm (Accessed on August 2, 2014); The Washington Herald, September 11, 1918, p. 6.

- Army Engineers in WW1, http://www.wwvets.com/Engineers.html (Accessed on August 2, 2014).

- “Honors Former Employee: District Building Flag at Half-mast for Capt. O.L. Housel,” The Washington Post, November 16, 1920, p. 14.

- “Memorial Statue to D.C. Heroes to Be Unveiled Here Tomorrow,” The Washington Herald, April 5, 1920, p. 5.

- “2004 Orange and Blue Book,” p. 134, http://grfx.cstv.com/photos/schools/ill/sports/m-footbl/auto_pdf/2004Guide-4.pdf (Accessed on August 2, 2014); www.fightingillini.com/facilities/memorialstadium.html (Accessed on August 3, 2014).

- Williams Death Certificate, on www.ancestry.com (Accessed on August 3, 2014).

- District of Columbia, Selected Deaths and Burials, 1840-1964, on www.ancestry.com (Accessed on August 3, 2014).

- “France Pays Tribute to U.S. Naval Heroes at Feb. 22 Exercises,” The Washington Times, February 18, 1920. p. 4.

- “Johnny Arthur Didway, Yeoman, U.S. Navy, Marion County, Indiana,” on www.wwvets.com/Navy.html (Accessed on August 4, 2014).

- The Washington Herald, October 3, 1918, p. 9.

- http://1914-1918.invisionzone.com/forums/index.php?showtopic=8962&page=9;

http://archive.org/stream/jstor-4243728/4243728_djvu.txt (Accessed on August 6, 2014).

- Cherrydale nomination form for Register of National Historic Places.

1910 Federal Census, on www.ancestry.com (Accessed on August 5, 2014).

- http://www.naval-history.net/WW1NavyUS-CasualtiesChrono1918-10Oct1.htm (Accessed on August 6, 2014).

- “First Memorial Tree Planted in Virginia,” The Washington Times, May 28, 1919, p. 4.

- 1900 Federal Census, on www.ancestry.com. (Accessed on August 5, 2014).

- “In Boy Scout Ranks,” The Washington Post, September 26, 1915. p. 7; “Boy Scout Notes,” The Washington Post, October 24, 1915, p. 14.

- “Gives Her Two Sons, Both Under 20, to U.S.” The Washington Times, July 4, 1917, p. 1.

- “Company H, of Old D.C. Guard, Lands in New York,” The Washington Times, May 20, 1919, p. 1.

- “Harry R. Stone,” on www.findagrave.com (Accessed on August 4, 2014).

- Ruth P. Rose, “The Role of Frank Lyon and His Associates in the early Development of Arlington County,” Arlington Historical Magazine, October 1976, Vol. 5, No. 4, p. 49. Personal information about John’s family life is attributed to Margaret Lyon Smith.

- “Western High School Graduates,” The Washington Times, June 13, 1910, p. 2.

- “Only County Man Killed,” The Alexandria County Monitor,” September 1, 1919, p. 1.

- http://www.civfed.org/historys.htm (Accessed on August 11, 2014).

- The Washington Times, May 11, 1915, p. 13.

- “At the Front: First of John Lyon’s Letters Received Not Censored by Military Authorities,” The Alexander County Monitor, October 8, 1915, pp. 7-8.

- “At the Front,” The Alexandria County Monitor, September 10, 1915, p. 6.

- Passport Renewal, December 8, 1915, on www.ancestry.com (Accessed on July 5, 2014); New York Passenger Lists, 1820-1957, on www.ancestry.com (Accessed on July 4, 2014).

- “Soldier Would Like to Have Bernhardt Visit Guardsmen on Border,” The Washington Times, August 28, 1916, p. 4.

- Walter Hines Page and Arthur Wilson (April 1916) The World’s Work (Doubleday, Page & Co.), pp. 584–593.

- “Co. G Leaves for Camp: Thousands Gather in Alexandria to Bid Soldiers Good-by,” The Washington Post, p. 8.

- “Special Designation Listing,” United States Army Center of Military History, www.history.army.mil/documents/ETO-OB/29ID-ETO.htm (Accessed on August 11, 2014).

- “Lieut. John Lyon Killed in Action,” The Washington Times, November 20, 1918. p. 15.

- 29th Infantry Division (Light): “Blue and Grey,” www.globalsecurity.org/military/agency/army/29id.htm (Accessed on August 13, 2014).

- “Lieut. John Lyon Dies In Action; Virginia Man,” The Washington Post, November 21, 1918, p. 9.

- “District Boy Killed Trying to Save Major,” The Washington Herald, August 4, 1919, p. 5.

- Archives of the Veterans of Foreign Wars, John Lyon Post #3150.

- “Decorations and Medals / Military / Decorations and Medals / Distinguished Service Cross,” http://www.tioh.hqda.pentagon.mil/Catalog/Heraldry.aspx?HeraldryId=15238&CategoryId=3&grp=4&menu=Decorations%20and%20Medals&ps=24&p=0 (Accessed on August 13, 2014).

- “Homage is Paid to G.U. Heroes,” The Washington Herald, December 6, 1920, p. 2.

- “Post Names of D.C. Heroes,” The Washington Times, April 11, 1921.

- “Tablet Unveiled for Hilltop Boys Who Died in the War,” The Washington Herald, June 14, 1921, p. 2.

- “Georgetown Elms Dedicated in Honor of War Sacrifices,” The Washington Post, May 31, 1927, p. 18.

- Draft Registration, June 5, 1917, www.ancestry.com. (Accessed on August 13, 2014).

- The Evening Star, April 21, 1900, p. 25; The Evening Star, April 6, 1901, p. 22; The Evening Star, May 31, 1902, p. 25; The Evening Star, September 6, 1902, p. 22.

- 1900 and 1910 Federal Census, www.ancestry.com. (Accessed on August 14, 2014)

- Draft Registration, on www.ancestry.com (Accessed on August 14, 2014).

- On www.usmilitariaforum.com/forums, posted on October 29, 2006 (Accessed on August 14, 2014).

- “World War I: Origins of “The Sightseeing Sixth” Infantry Division,” http://www.capmarine.com/genealogy/PaulWWILetters/index.htm (Accessed on August 14, 2014).

- “Post Names of D.C. Heroes”

- 1900 and 1910 Federal Census, on www.ancestry.com (Accessed on August 13, 2014).

- Nomination for National Register of Historic Places, Secton 8, p 1, on www.scribd.com/doc/119187753/Robert-Gould-Shaw-Junior-High-School-f-k-a-McKinley-Manual-Training-School-n-k-a-Asbury-Dwellings-650-Rhode-Island-Avenue-NW-in-the-Shaw-neighborhood (Accessed on August 13, 2014).

- “The Signal Corps’ Roll,” The Washington Times, June 24, 1916, p. 2.

- “The Department of Commerce Announces the Following Changes in its Personnel,” The Washington Post, January 14, 1917, p. F2.

- 1918 US Army Signal Corps/ US Army Air Service Accident Reports, http//www.aviationarchaeology.com/src/1940sB4/1918.htm (Accessed on August 16, 2014).

- https://www.eaa.org/en/eaa-museum/museum-collection/aircraft-collection-folder/1918-curtiss-jn4d-jenny (Accessed on August 16, 2014); http://www.flyingheritage.com/TemplatePlane.aspx?contentId=25 (Accessed on August 16, 2014).

- Barbara Ganson, Texas Takes Wing: A Century of Flight in the Lone Star State (University of Texas Press, 2014), p. 33.

- Draft Registration, on www.ancestry.com (Accessed on July 12, 2014).

- 1910 Federal Census, on www.ancestry.com (Accessed on August 16, 2014).

- Report of Interment, on www.ancestry.com (Accessed on July 6, 2014).

- Black Americans in Defense of Our Nation, http://www.shsu.edu/~his_ncp/AfrAmer.html (Accessed on August 16, 2014).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.